Kraftwerk and Man as Industrial Palace

What can electronic music teach us about robots?

The members of Kraftwerk are often referred to as “the godfathers of electronic music.” While they are pioneers of the use of electronic equipment in music, they have also had considerable influence on disco, rap, electro, synth-pop—a ubiquitous influence from Detroit techno to London grime. From their home in Germany, they have created a legacy that has had an enduring effect and has informed the development of pop culture for over fifty years. My wife and I had the good fortune to see their live 3D performance in Dallas back in June, and my colleagues suggested I write a “Power Play” piece about it. The more I thought about it, the more I liked the idea. And seeing as kraftwerk means “power plant,” that should naturally interest readers of Power Transmission Engineering.

As we know, a power plant is an engine and related parts supplying the motive power of a self-propelled object. And Kraftwerk was modeled after the man-machine (die mensch-maschine), a concept inspired by German polymath Fritz Kahn who laid the foundations of modern information graphics and is best known today for his famous 1926 poster Man as Industrial Palace.

What can Kraftwerk teach us about robots? The answer is both very little and a lot. For Kraftwerk, the man-machine is a philosophical and acoustic concept with the group functioning as the power plant—the ultimate fusion of culture and technology. Not the role of technology in an as-yet-unrealized future, but the integration of technology and human life in the present.

For Kahn, factories, engine rooms, and laboratories do not work on their own but are operated and driven by large numbers of workers. These human figures keep the man-machine running. In Kahn’s pictorial world, he sees metaphysics and science not as opposites but as two sides of the same coin, or as he put it, the “heaven and earth of the human soul.”

As Kraftwerk has often claimed, “The machines are part of us, and we are part of the machines. They play with us, and we play with them. We are brothers.” These ideas were given concrete form in The Man-Machine album of 1978, which showed Kraftwerk’s relationship to technology is bound up in their relation to their immediate environment—rather than using postmodern technology to map out an escape route towards the further reaches of the cosmos, it is used to recreate the mechanized soundscapes of the modern, industrialized city.

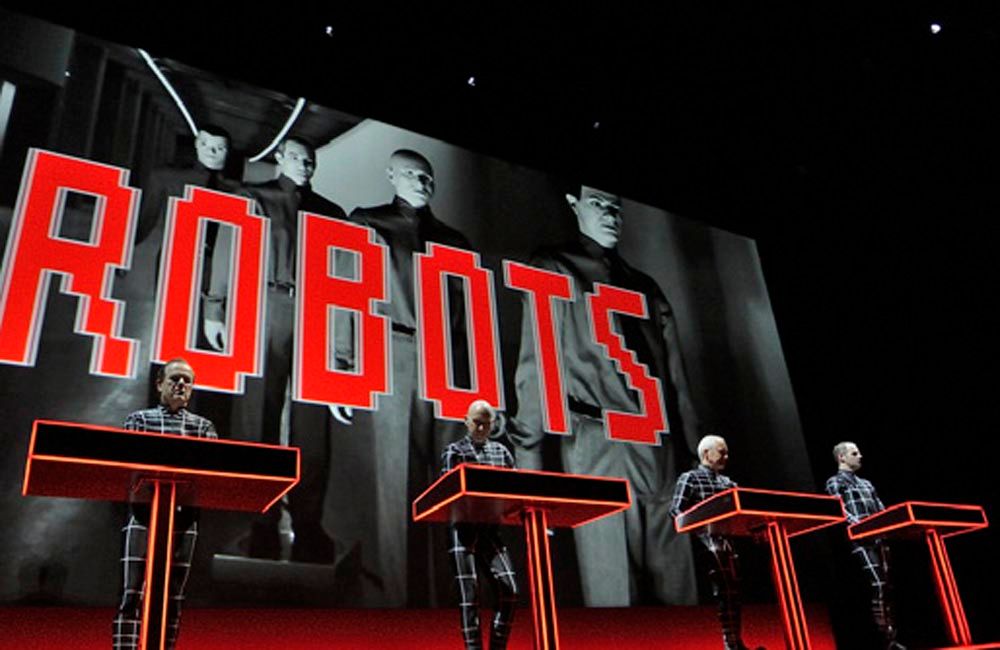

As my wife and I entered the Music Hall at Fair Park in Dallas we were given 3D glasses and directed to our seats on a balcony which gave us an angled view down to the stage. At 7:00 p.m., the four members dressed in matching grid suits took to their iconic control desks all outlined in neon changing color synchronized with the music. At times, against the backdrop of 3D visuals, the four members seem to be suspended in space. In his seminal novel Neuromancer (1984), William Gibson prophetically coined the term “cyberspace” which he described as a “consensual hallucination,” which perfectly captures the live experience of Kraftwerk’s futurist aesthetic. The aural and visual synesthesia was so perfectly integrated we were swept away in a hypnotic state that felt closer to a consensual hallucination than anything originating from the gigantic screens and speakers.

Kraftwerk once said in an interview, “When you play electronic music, you have control of the imagination of the people in the room and it can go to the extent where it’s almost physical.” This sentiment is further echoed in another interview in which they say, “Kraftwerk finds some energy in the environment of people who come to see us and who make us play in another dimension. Electronics are beyond nations and colors. It speaks a language everyone can understand. It expresses more than just stories the way most conventional songs do. With electronics, everything is possible. In front of the loudspeakers, everyone is equal.”