A New Standardizable Calculation Method to Predict the Efficiency of Worm Gear Drives

A New Standardizable Calculation Method to Predict the Efficiency of Worm Gear Drives

Manuel Oehler, Balázs Magyar and Bernd Sauer

Introduction

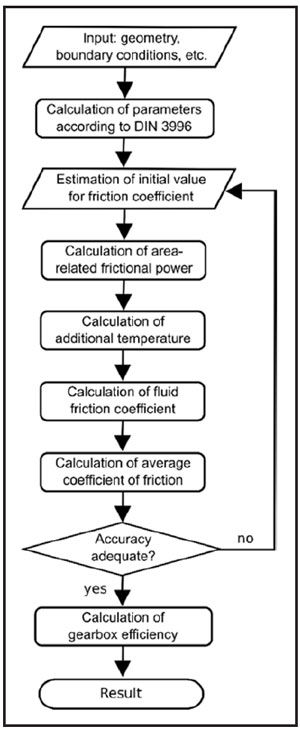

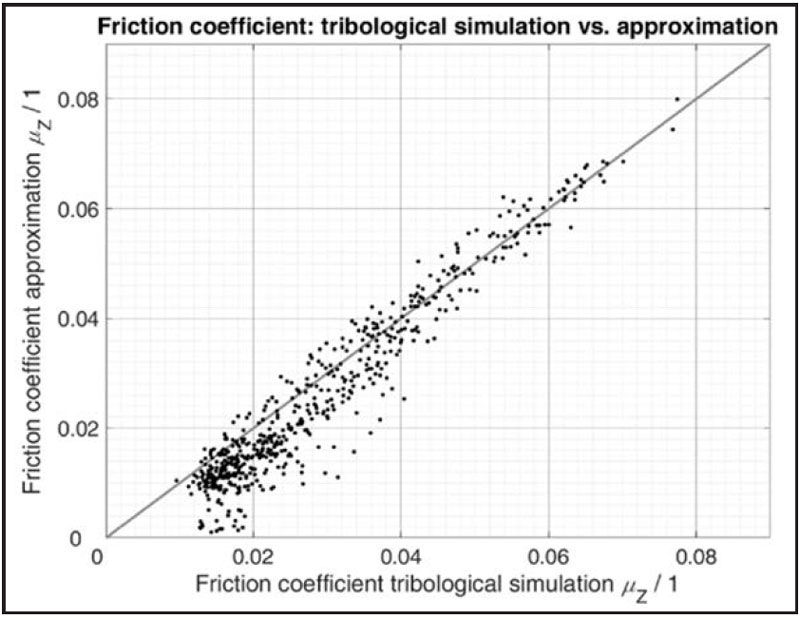

Within the scope of the research project FVA 729 I “Worm Gear Efficiency,” a physically based simulation method for the efficiency of worm gear drives was developed. This method is validated by experiments with different gear sizes and ratios. An extensive parameter study with the use of this simulation program was carried out to specify the magnitude of various influencing variables on the efficiency. The large parameter field for this study was created with design of experiments (DoE) to take into account a wide range of different parameter combinations. Based on the principle of similarity, the method of dimensional analysis was applied to derive an approximation equation for the efficiency in order to make the developed method accessible to broad practice. The derivation of this new, physically based formula using dimensionless influencing parameters is the object of this paper. The resulting tool allows calculation engineers to compare different drivetrain concepts with regard to efficiency. These easy-to-handle formulas can be incorporated into the standard DIN 3996.

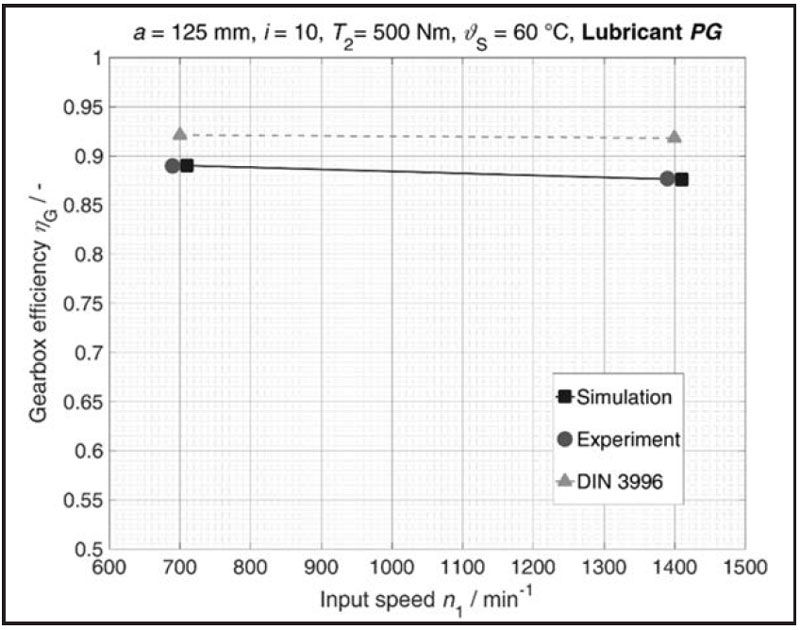

Worm gearboxes are characterized by the large gear ratios that can be realized in a single stage, as well as by low-vibration- and low-noise-running behavior, compared to other gear transmissions. These positive properties, however, are associated with a lower efficiency compared to helical gearboxes, due to the high sliding velocities in the tooth engagement resulting from the intersecting axes. In order to be able to design efficient drive solutions, various transmission types and design variants must be comparable with each other in terms of the expected operating efficiency during the design phase. The approximation equations described in the German standard DIN 3996 (Ref. 1) are based on quasi-stationary measurements of gearboxes with a gear ratio of i = 20.5 and with a center distance of a = 100 mm. The transferability of the existing and partly standardized empirical formulas to other sizes and gear ratios is only possible to a limited extent. For this reason there is a need on the part of industry to expand the field of use of the calculation method in a broad range of sizes and gear ratios. The aim of this work is the development of a physically based simulation method which is verified by experimental results in order to reliably determine the efficiency of worm gear drives. Included in the investigations are various sizes, gear ratios and oil types, as well as stationary and transient operating conditions. The efficiency calculation of worm drives is based on theoretical principles, taking into account the different interactions of the influencing variables. This theoretical work is supplemented by random running trials and tribological investigations that provide input data for the calculations. This results in a physically based simulation model with which worm gearing can be investigated in a variety of ways. The target variables are, among other things, the local and the mean tooth friction coefficients, as well as the gearing and overall efficiency of the gearbox under test. The average gear friction coefficient can also be used to check the transmission for possible self-locking or self-braking.

Tribological Simulation

Magyar studied ZK-type cylindrical worm gears as part of his dissertation at the Institute of Machine Elements, Gears and Transmissions (MEGT) with regard to the tribological and dynamic behavior, both experimentally and simultatively (Ref. 2). In his work a calculation model was developed based on the work of Bouché (Ref. 3). Thus, the local tooth friction coefficients and the overall efficiency of worm drives operating in the mixed friction area can be determined by means of the TEHD theory in quasi-stationary operating conditions. The simulation model was verified with own test results. This calculation approach is the starting point of this work.

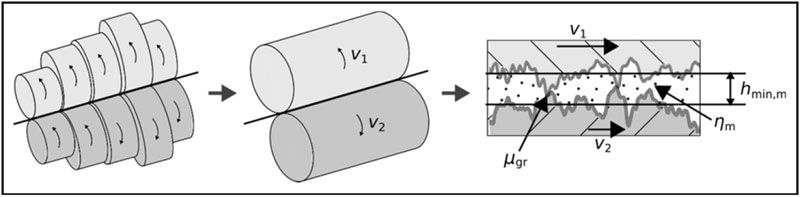

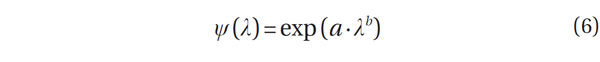

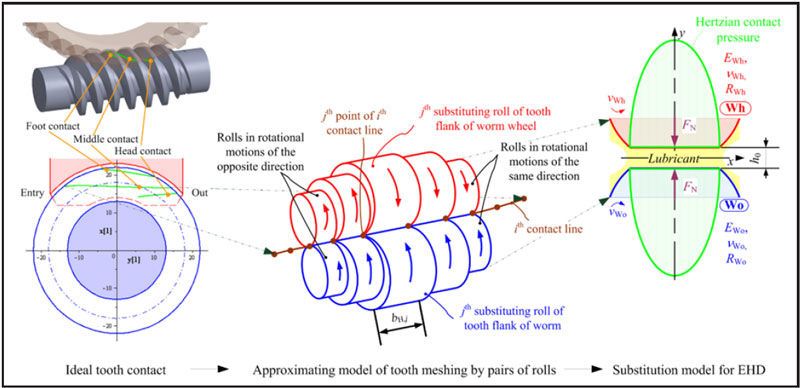

To calculate the locally variable tooth friction coefficients of worm gears, the theoretical contact lines are determined first (Fig. 1, left). The calculation of the radius of curvature at the points of contact and the discretization of the contacting tooth flanks by rotating rollers follows (Fig. 1, middle). In order to be able to model the kinematic conditions of the worm and worm wheel, the points in the contact zone are modelled with the aid of rotating rollers. Considering the kinematic behavior of the gears, the sliding and sum velocities in every point of the contact lines are calculated. The lubricating gap height is determined under the assumption of a Hertzian pressure distribution (Fig. 1, right).

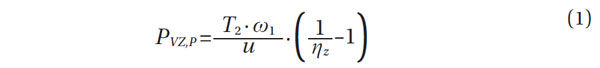

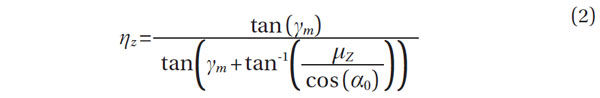

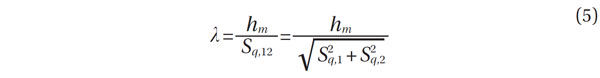

Knowing the film thickness of the lubricant and using pre-calculated division curves for the load-carrying contact ratio derived from a self-developed software, the rate of boundary lubrication can be calculated for each rotating pair of rollers. The heat conditions in the contact zone are determined in an iterative manner by simultaneously solving the differential equation for Fourier’s law of heat conduction and the simplified energy equation of the lubricant. With a known lubricant temperature, the viscosity and the fluid friction force dependent on this viscosity can be calculated for all pairs of rollers. Subsequently, the calculation of the coefficient of mixed friction follows, which corresponds to the local friction coefficient between the gears. A more precise description of the procedure of this method can be found (Ref. 2). According to the knowledge of the local tooth friction coefficients, these can be averaged and thus the total efficiency of the gears ηz and the gear power loss PVZ,P can be calculated.