Turning Science Fiction Into Fact

Aerospace Competition Aims to Make Space Elevator a Reality

Matthew Jaster, Associate Editor

Conceptual art on the space elevator courtesy of The Spaceward Foundation.

The Space Elevator Games will begin in September 2008.

Fans of Arthur C. Clarke may remember a concept in his 1979 novel, The Fountains of Paradise, of an orbital elevator used to raise payloads from the ground to a satellite as a more cost-effective means of transporting material to outer space. NASA claims that Clarke was asked at a conference in 1979 how long it would take to actually produce such a device and he sarcastically remarked, “Probably about 50 years after everybody quits laughing.”

While the idea of a space elevator does sound a bit far-fetched, it didn’t stop a group of scientists and engineers from discussing the possibility of designing one. Working under the NASA Institute for Advanced Concepts Phase II grant, Bradley C. Edwards, Ph.D., had the objective of producing initial designs. He would soon be widely recognized as the developer of the modern space elevator.

After years of debates on materials, available technology and funding, Edwards and his engineering team believe a space elevator could be operational in the next 15–50 years. It was once estimated to take more than 300 years to produce the space elevator, but major developments in carbon nanotubes and power beaming have significantly raised the stakes and altered the timetable.

A Railroad to Space

The biography for Ben Shelef at www.spaceward.org says it all. “An aerospace engineer by day, Ben dons the mask and cape of space crusader by night and engages in daring escapades such as space elevator games and robotic challenges.” Shelef, co-founder of The Spaceward Foundation, says conducting a project that basically brings science fiction to life is “by far the most inspiring thing one can work on.”

The Spaceward Foundation is one of many non-profit organizations participating in NASA’s Centennial Challenge Program, an annual competition awarding prize money for innovations in aerospace technology. The foundation’s main objective is to get the right people in both the aerospace and academic fields thinking about the technology needed to design and construct the space elevator. Shelef is optimistic that the knowledge gained through these yearly competitions will move NASA one step closer to actual production.

The space elevator is a climbing mechanism that can travel beyond Earth’s gravitational pull from an anchor on the Earth to a counterweight beyond geosynchronous orbit. Cargo and passengers could “ride” the climbing mechanism in a straight line up into space. Shelef explains what exactly a trip on a space elevator might entail:

- The “lobby” would be an anchor station at sea level.

- Points along the line used to jump off to lower orbits.

- The GEO point, where you step off and are in perfect geosynchronous orbit (36,000 km above sea level).

- Points along the line used to jump off to interplanetary trajectories (going to Mars, asteroids, etc.).

- Counterweight, the end of the line, the roof floor where only elevator technicians can go (100,000 km above sea level).

The elevator can best be described as a physical railroad to space that runs via a cable, theoretically 25,000 miles long. Until the early 1990s, few in the science community believed a material existed strong enough to support such an operation. With the discovery of carbon nanotubes—a material that contains extraordinary mechanical properties—scientists were confident the space elevator could be produced.

The Space Elevator Games

According to the website, The Spaceward Foundation is managing two engineering competitions, known as The Space Elevator Games, on topics such as tether strength and power beaming to further space elevator research.

One of the more appealing aspects for Shelef is the number of commercial organizations involved in the competition. Companies like Bosch Rexroth, G2 Engineering, Access I/O, Gizmonics and Trumpf Laser are contributing material in the hopes of advancing the technology.

In the strong tether competition, teams test and measure the tensile strength of the proposed elevator tethers. In order to make the experiment exciting, the foundation created a head-to-head strength competition between engineering teams.

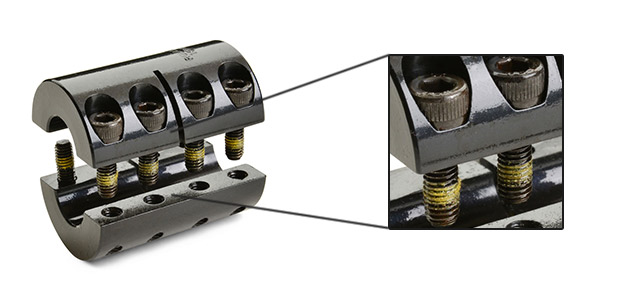

The tether pull machine used in the competition is a boxlike structure about 12 feet long and 18 inches high. The tethers are connected to the machine end-to-end to run a comparative test between two samples. Essentially, the machine grabs the two samples at their respective ends and pulls their free ends toward each other. As the force increases, one will break and the other is declared the winner.

Shelef recalled using an aluminum framing product from Bosch Rexroth for his day job and thought it would work for the space elevator competition. Since 2005, the Bosch Rexroth framing has been an intricate part of the tether competition.

The tether pull machine can be assembled quickly using Bosch Rexroth connectors and the aluminum framing unit is reusable. This allows for some flexibility if design teams need to make any changes or adjustments during the competition.

Kevin Gingerich, marketing services manager for the linear motion/assembly branch at Bosch Rexroth, is pleased the company participates in innovations like the space elevator project.

“The Space Elevator Games, for us have a twofold purpose,” Gingerich says. “One is to achieve a certain public relations presence to an audience that is operating in the realm of science fiction. These engineers and scientists are innovative thinkers, and we’re more than happy to offer a product that can be used in a unique way. More importantly, it’s just a neat thing for Bosch Rexroth to be a part of.”

Although the framing Bosch Rexroth provides won’t actually be used in the elevator itself, it plays a pivotal role in the test rigs for the tether competition. Shelef hasn’t ruled out the possibility of Bosch Rexroth hardware being used elsewhere. “Perhaps in the optical components of the laser,” Shelef says.

Bosch Rexroth provides the aluminum framing for the strong tether competition.

When the competition first began in 2005, organizers wanted a 50 percent improvement in breaking force from year to year. The 2007 competition produced mixed results.

“The standard material-based tethers performed the same,” Shelef says. “The first carbon nanotube tether showed up last year, but was not closed to a loop so it wasn’t measurable. The next sample will be ready to measure in September 2008.”

In addition to the tether tests, researchers have been working on solutions to power the electric cars (known as climbers in space elevator jargon) that travel up and down the elevator. The biggest obstacle in this portion of the project is powering the cars. Typically, the fuel or batteries end up weighing more than the cars can lift.

Dr. Edwards came up with a solution in 2000 while working at the Los Alamos National Laboratory. He called his technique power beaming. In power beaming, the electric cars carry photo-voltaic cells that face back towards Earth. The ground station projects a laser beam at the cars, which in turn converts the light into electricity to drive the motors. The main benefit of this method is that it allows the scientists to leave the fuel tank on the ground, making the cars very lightweight.

The Spaceward Foundation hosts a power beaming competition in which teams build mechanical devices that propel themselves up a cable. The challenge is to receive the transmitted power and transform it into mechanical motion. Beamed power competitions in 2006 and 2007 produced noteworthy results, but no team has been able to meet the criteria to claim the cash prize.

The strong tether competition tests the tensile strength of proposed elevator tethers.

For the 2008 competition, teams will be expected to drive their laser-powered devices up a cable 5 m/s over 1 km (10 times as high and twice as fast as the 2007 competition). Trumpf Laser is providing an 8 kW laser beam to interested teams participating in the power beaming competition.

“We’ll provide the entire engineering and management that goes with the installation and transport of the equipment to and from the competition site,” says Dr. Holger Schlueter, vice president of Trumpf Laser division. “In addition, we offer teams the necessary training on the equipment, provide support for the optical, electrical and mechanical integration, set and monitor safety standards and conduct several test runs for the teams that participate.”

Schlueter says that Trumpf initially got involved in the project because the space elevator competition gives worldwide visibility to laser technology.

“We believe there is a future market for high-quality, high-average power distribution through laser beams,” Schlueter says. “This competition provides a unique opportunity for visibility into sectors that otherwise might never have considered lasers or Trumpf as a solution provider.”

Trumpf plans to provide support at this year’s competition, and if the prize in power beaming is not claimed in 2008, they are committed to supporting it again next year.

One Step Closer to Reality

Shelef is excited the foundation is making a substantial mark in aerospace technology with advancements in space elevator research. The space program, in general, has suffered somewhat of an identity crisis in the last 20 years. Math and science in the classroom isn’t as popular as it was years ago and the general population sees less practicality in spending millions on space research projects.

The Spaceward Foundation aims to change that. It intends to get young minds interested again in the space program. It also hopes to inspire adults who may have forgotten how important the U.S. space program is to the future of exploration and commerce.

The commercial companies supporting the program have already discovered several advantages to participating in the space elevator competition.

“We see that we are of interest to a whole new group of engineering students that would like to work for Trumpf, which is a very attractive side effect for us,” Schlueter says. “Some of these students are active in space elevator projects; others have heard about it in the news and are interested in a company that does such cool things.”

Trumpf Laser is providing the TruDisk 8002 laser for the power beaming competition.

Gingerich adds that Bosch Rexroth might find it challenging to draw a line between cutting edge technology and science fiction, but that won’t prevent the company from continuously pursuing such projects.

“We’re always trying to develop material that can help our customers be as productive as they can be. Often that means taking some risks at the forefront of technology,” Gingerich says. “Ben Shelef is an entrepreneur and an impresario. Through the force of his own will, he’s driving this space elevator technology forward, and we’re happy to support the process.”

As Shelef prepares for the next wave of competitions this September, there’s a feeling of anticipation that the team is getting closer to making significant progress. When asked for an “unofficial” timetable for the project, Shelef responds quickly.

“Our current estimate is to show strong carbon tethers by 2010, show space elevator-strong carbon nanotube tethers by 2020 and have the space elevator working by 2030,” Shelef says.

Some may call that optimistic or overconfident; just don’t tell The Spaceward Foundation team it’s impossible.